December 6, 2025 | 19:02 GMT +7

December 6, 2025 | 19:02 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

December 6, 2025 | 19:02 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

More than a tourist attraction, the 160-year-old Saigon Zoo and Botanical Gardens is emerging as a model of wildlife disease prevention, right in the heart of Ho Chi Minh City. Home to 1,858 animals across 131 species, including rare Indochinese tigers, scimitar-horned oryx, flamingos, yellow-cheeked gibbons, and Javan pangolins, the zoo has transformed into a frontline facility for wildlife health monitoring and public education.

Food for wild animals at the Zoo is strictly controlled from the supplier to the cage, helping to avoid unwanted incidents. Photo: Le Binh.

Every animal at the zoo has an individual health record documenting vaccinations, lab tests, treatments, dietary plans, and behavioral observations. A dedicated veterinary team maintains these records, working closely with caregivers and zookeepers assigned to specific enclosures.

Mai Khac Trung Truc, Director of the Animal Division, described their strict quarantine system: triple-layered fencing, double-entry doors with disinfectant pits, and personal protective gear for all staff,

including boots, gloves, masks, and specialised uniforms. "This not only keeps pathogens out, but also helps animals gradually adjust to human presence in their new environment," he explained.

The zoo sources food only from certified suppliers, and each batch is inspected before being distributed to the animals. Samples from each food lot are retained to allow traceability in case of contamination. “We test before serving and tailor preparation to each species. Every step is tracked, from quality inspection to feeding,” said Truc.

Injuries from animal conflicts are the most common medical cases. Still, meticulous attention is given to everything from feeding trays to bathing pools. Keepers observe leftover food to assess animal health and adjust care accordingly. A 24/7 camera system ensures that zookeepers respond to emergencies within five minutes.

The most common zoo illnesses are mainly injuries caused by animals fighting each other. Photo: LB.

“Understanding an animal’s ‘language’ is crucial,” Truc said. “For predators like tigers or bears, a slight change in eye contact or gait can signal illness. Recognising those signs early makes all the difference.”

All animals are vaccinated based on species-specific risks. Rare birds receive flu or Newcastle virus shots, while carnivores and primates get annual rabies boosters. Incoming animals are quarantined and tested before integration.

Unlike many captive facilities in Vietnam, Saigon Zoo has implemented a full suite of disease prevention measures: electronic medical records, periodic health checks, infectious disease screening, tailored vaccination schedules, and close collaboration with research institutions for laboratory diagnostics.

Thanks to these precautions, the zoo has remained disease-free throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, even among virus-sensitive species. After news of the H5N1 avian flu outbreak in Dong Nai, the zoo immediately tightened biosecurity protocols and increased clinical monitoring of all carnivores.

"We can’t afford to be complacent,” Truc emphasized. “Cross-species transmission is a real threat. So we train all staff, not just vets, to monitor behavior, wear protective gear, and respond rapidly to any warning signs”.

The tiger was diagnosed by veterinarians with images and regular medical check-ups. Photo: Saigon Zoo and Botanical Garden.

The zoo’s approach is not just about animal care, it’s a powerful public education tool. Through field trips and outreach programs, students learn about the connection between human, animal, and environmental health. These lessons help promote the “One Health” mindset, a growing global movement that sees health as interconnected across species and ecosystems.

Experts believe that replicating the Saigon Zoo’s practices in wildlife rescue centers, national parks, and private breeding facilities could drastically reduce disease surveillance blind spots nationwide, an urgent priority in the wake of recent zoonotic disease scares.

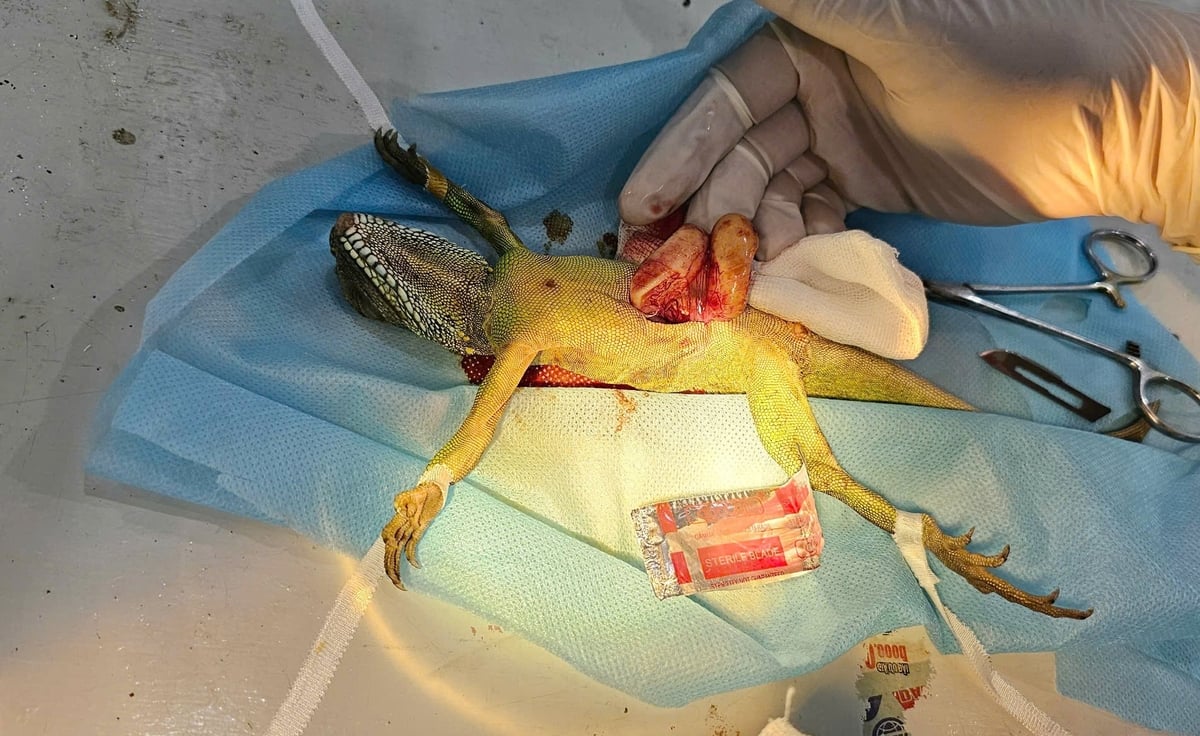

One recent example: zoo veterinarians successfully performed surgery on a water dragon suffering from egg-binding, a condition that would likely have gone undetected in less-equipped settings.

"If a zoo in Ho Chi Minh City can do it, there's no reason larger facilities elsewhere can't, given the right will and resources," argued Assoc. Prof. Le Quang Thong of Nong Lam University. He called for minimum national standards on health care for captive wildlife.

A dragon was operated on by a veterinarian to treat blocked eggs. Photo: LB.

But scaling this model requires more than good intentions. It needs unified action from city governments, the veterinary sector, forest rangers, and Vietnam’s still-underdeveloped wildlife health research and training infrastructure. A single zoo can’t bear the burden alone.

Saigon Zoo is more than a place to view rare animals, it’s living proof that professional, systematic wildlife health care is achievable. In an age where zoonotic diseases can jump from animals to humans in a matter of days, these lessons from a city zoo may be the key to safeguarding public health far beyond its gates.

Translated by Linh Linh

/2025/12/02/2629-3-141849_60.jpg)

(VAN) Based on its large-scale planted forests, several rubber enterprises have proactively conducted greenhouse gas emission inventories in preparation for entering the forest carbon credit market.

(VAN) MAE is leading in developing a national rare earth strategy, which will be submitted to the competent authorities for promulgation in early 2026.

/2025/12/02/4006-4-092040_652.jpg)

(VAN) The model of converting low-efficiency rice land to aquaculture in many localities has helped increase incomes by 5 to 15 times, improve the environment, and form new fisheries economic zones.

(VAN) Funded by ACIAR, Project FST/2020/123 focuses on measures to prevent harmful alien species, thereby protecting forests from invasive threats.

(VAN) The National Assembly's Supervisory Delegation pointed out solutions for the blue economy, circular economy, environmental protection, and technology application for sustainable marine governance.

(VAN) Lao Cai’s forestry sector is stepping into the spotlight with a series of pioneering initiatives in forest management, monitoring, and sustainable development aimed at generating carbon credits.

(VAN) The Provincial Competitiveness and Governance Index (PCGI) is a tool designed to reflect the quality of local governance.