November 12, 2025 | 15:51 GMT +7

November 12, 2025 | 15:51 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

November 12, 2025 | 15:51 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

Against this backdrop, agroecology has emerged as a scientifically grounded and practical pathway for transformation. Dr. Éliane Ubalijoro, Executive Director of CIFOR-ICRAF and Director General of ICRAF, observed: “We know our food systems are broken, producing malnutrition, food waste, biodiversity loss, land degradation and climate change. But we also know that there is a great opportunity for transformation by harnessing the knowledge and solution already in use, and one of those solutions is agroecology”.

She describes it as a vision of farming that “nourishes both land and people”, with the health and prosperity of future generations as the benchmark, rather than vague promises.

Dr. Éliane Ubalijoro, Executive Director of CIFOR-ICRAF and Director General of ICRAF. Photo: ICRAF Vietnam.

The first advantage of agroecology lies right under farmers’ feet—the soil. When cropping systems are designed around ecological principles, fertility is restored, microbial life thrives, soil structure improves, and water retention increases. Healthier soil reduces the risk of crop failure under extreme weather. This is not just a technical factor but a foundation of climate resilience, where each harvest is no longer left to chance.

Above ground, crop diversity and adaptive practices ease pest pressures, reducing reliance on external inputs. That shift alters the cost-benefit balance: variable costs fall, while net profits rise. For smallholders, improved yields and income are often critical to survival, and agroecology provides a holistic means to achieve this.

For consumers, agroecology expands access to safer, more nutritious food, helping curb the global surge of non-communicable diseases. Well-managed seasonal supplies and organised local value chains diversify diets and narrow nutrition gaps. This public health benefit is measurable through reduced treatment costs in the long run, an overlooked “return” embedded in agriculture at the national level.

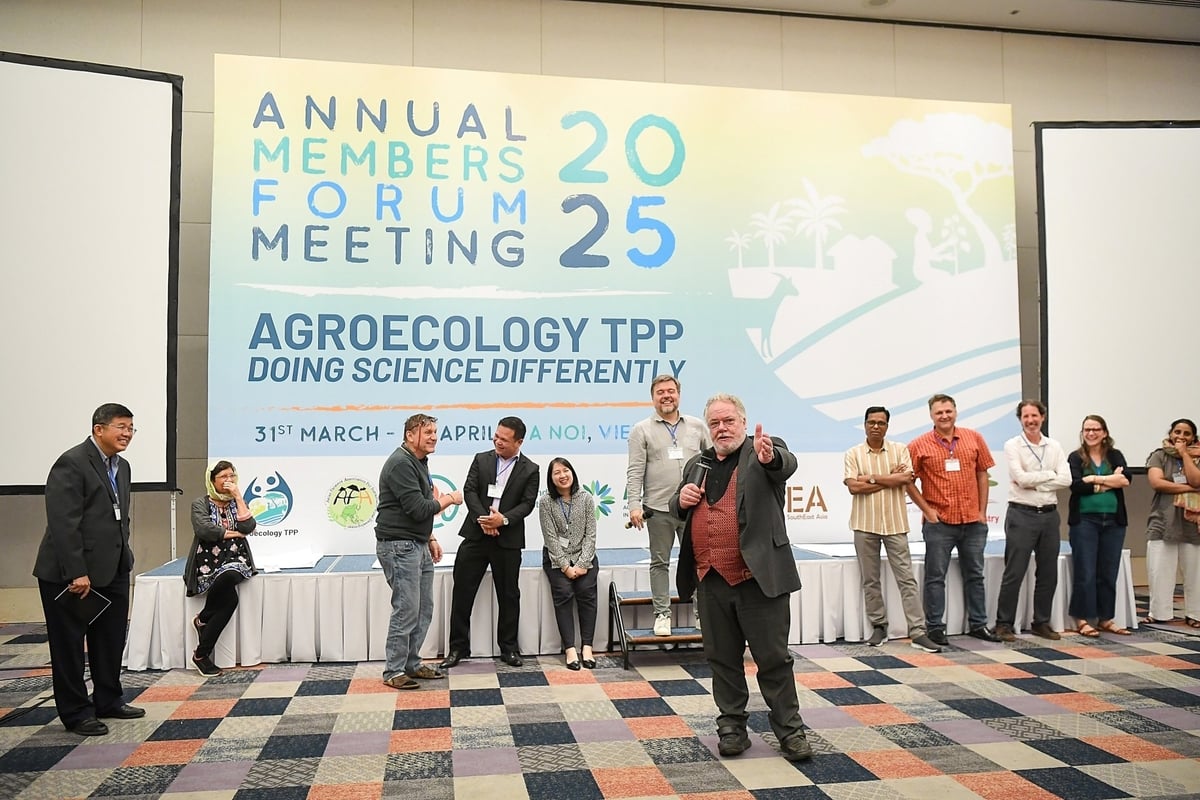

The annual meeting of the Agroecology Transition Partnership Platform (Agroecology TPP) was held in Hanoi from March 31 to April 4. Photo: ICRAF Vietnam.

The economic potential extends beyond farm gates. Agroecology encourages product and service diversification, from fresh produce to processed goods, from organic materials to agro-tourism. Each link adds jobs per hectare, strengthening local economies. Maintained landscapes, in turn, support ecotourism and experiential education, creating income streams beyond farming seasons.

At the policy level, agroecology integrates rural development with conservation and climate goals. When production aligns with nature, external costs such as water pollution, soil degradation, and biodiversity loss shrink, easing fiscal pressure on environmental budgets. Agroecology does not aim to “repair” ecosystems after production, it designs production so ecosystems remain healthy.

It also fosters space for blending indigenous knowledge with modern science. Farmers’ observations of winds, flows, and pest cycles, combined with experimental data and analytical tools, yield flexible, context-specific solutions. Farmers are no longer passive recipients but co-authors of innovation.

Agroecology is seen as a solution to many of today’s global challenges. Photo: ICRAF Vietnam.

The promise is real, but scaling agroecology requires stronger operational capacity. Professor Fergus Sinclair, Co-Convenor the Agroecology Transition Partnership Platform (Agroecology TPP), raised a key question: "But of course, farmers are not going to read a scientific journal, so how do we make it available?" Knowledge confined to journals cannot change fields.

The gap must be bridged, first, through training. Agronomy curricula remain heavily focused on intensive farming, with agroecology scattered across modules. Farmer-to-farmer learning and hands-on training should be built into public–private support funds. Seeing results in their own fields is more convincing than any slideshow.

Second, through communication. Dr. Pierre Ferrand of FAO stressed: “We need to find a creative way also to communicate better the research. Creativity on how we translate into materials that is better understood by different audiences ... and if we really want a transformative change for food system, it's important to have a messages that tailored for different audiences."

In agroecology, indigenous knowledge of livestock and crop farming is always encouraged. Photo: ICRAF Vietnam.

Third, through research. Agroecology is a “labyrinth” of soil biology, microclimate, market behaviour, and local institutions. Studied in isolation, it yields elegant reports but little impact in practice. Research must be interdisciplinary from the outset, pairing ecological models with economic and institutional analysis. Yet such studies often lack long-term funding, though agroecological outcomes take years to materialize. “Farmers shouldn’t just participate - they should decide what’s researched" argued Dr. Matthias Geck, CIFOR-ICRAF Nairobi and Agroecology TPP Coordinator, ensuring research outcomes stay rooted in reality.

Fourth, through policy and finance. Without green credit, climate insurance, or tax incentives for organic inputs, farmers face too much risk to change practices. Standards and monitoring must also be robust enough to capture genuine “green value”, avoiding token compliance. Effective policy follows the money: who invests, who bears risk, who benefits, and whether allocation creates real incentives.

At the intersection of these four bridges, Agroecology TPP offers a notable model. The platform creates a “co-creation space” where scientists, farmers, and policymakers draft shared roadmaps. Dr. Ubalijoro describes its goal as closing the gap between knowledge and practice, anchored in equity, where every voice counts. These roadmaps focus on scalable pilots with clear metrics and multi-year resources rather than “one-season budgets”.

The road to agroecology is not without hurdles. Farming habits are deeply entrenched. Traditional agriculture has built compatible skills and supply networks, so transformation is like changing an entire “operating system,” not just adding an app. A few training sessions cannot flip the switch; what’s needed is a phased roadmap. Choose leverage points, set visible interim goals, and measure transparently to build trust. Once positive signals appear, “neighbour effects” can draw more farmers in.

Another challenge is evidence. Agroecology's benefits unfold over time and space, making them hard to convert into immediate cash values. Measurement systems must be sensitive enough to track everything from smallholders' household economic costs to broader indicators like biodiversity and soil carbon.

Decisions must also be made closer to implementation. Local levels need authority to test, expand, and adapt. Provinces must tailor solutions by season, while national governments provide frameworks on standards, credit, and insurance.

A sustainable food system cannot be built on a single decision but through consistent, layered choices. Agroecology offers a feasible path: restoring soils, boosting resilience, improving nutrition, and strengthening local livelihoods. But fields will only truly change color when knowledge leaves the bookshelf, financing has staying power, and farmers’ choices are placed at the center.

Translated by Linh Linh

(VAN) Farmers in the Mekong Delta are advancing with a new production mindset, applying technology, protecting the environment, and creating sustainable agricultural value.

(VAN) From a small-scale industry, livestock production and animal health has become a concentrated, professional, modern technical economic sector.

(VAN) An Giang integrates IPHM to promote green rice farming, cut costs, and enhance grain quality and brand value.

(VAN) Marine resources beneath the sea are being gradually identified and studied, forming the foundation for sustainable exploitation and the development of a blue economy.

(VAN) Residents in the Lang Sen buffer zone can improve their income and preserve wetland biodiversity thanks to the nature-based livelihood models.

(VAN) The Department of Hydraulic Works Management and Construction aims to build a modern, smart, and sustainable water management sector that ensures water security and promotes rural development in Viet Nam.

(VAN) Dong Thap province stands before major opportunities in restructuring its economy, particularly in agriculture and environmental management, which have long been local strengths.