August 8, 2025 | 03:24 GMT +7

August 8, 2025 | 03:24 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

August 8, 2025 | 03:24 GMT +7

Hotline: 0913.378.918

The recent deaths of 20 tigers and a leopard from avian influenza (A/H5N1) sent shockwaves through Vietnam’s veterinary and wildlife conservation communities. More than a tragic event, the incident underscored alarming gaps in veterinary care and regulatory oversight for captive wildlife.

According to Thibault Ledecq, Conservation Director at WWF-Vietnam, returning wild animals to their natural habitats is ideal, but often unfeasible. Many animals lose the ability to survive in the wild due to habitat loss or poor health. In such cases, well-managed and legal captive facilities can play a vital role in both conservation and disease prevention.

At Cat Tien Wildlife Rescue Center in Dong Nai, staff now collect samples for avian flu and coronavirus testing immediately upon receiving animals. This represents a shift from simply caring for rescued animals to also positioning these facilities as disease surveillance hubs.

Veterinary staff at Cat Tien monitor the animals' health, conduct diagnostic tests, and administer necessary vaccinations before considering release. Each individual is tracked holistically, from food intake to lab results. Photo: Le Binh.

Still, as Ledecq pointed out, Vietnam lacks a unified veterinary standard for wildlife breeding facilities. To address this, WWF partnered with the Department of Forestry and the Forest Protection Department to host a technical workshop in September 2023, joined by experts from AAF and Four Paws. The result was a draft “Captive Tiger Management Framework,” which compiles recommendations on hygiene, feeding regimes, vaccination protocols, and diagnostic capacity, now being considered for broader application.

“Applying rigorous veterinary standards during captivity is not only about animal welfare”, Ledecq emphasized. “It’s critical to prevent future outbreaks like the one in Dong Nai”.

Associate Professor Le Thanh Hien from Nong Lam University in Ho Chi Minh City added that wildlife should never be farmed on a large scale. Only those who meet strict biosecurity standards should be licensed. This is the only way to ensure the disease doesn’t spill over to livestock or humans.

Some breeders are now collaborating with forest rangers and health experts on Dong Nai's private otter and python farms. They’ve installed thermal monitoring cameras, tracked feeding logs, and reported abnormalities in animal behavior.

“Meeting biosecurity requirements must be a prerequisite for any wildlife farming permit”, Hien stressed.

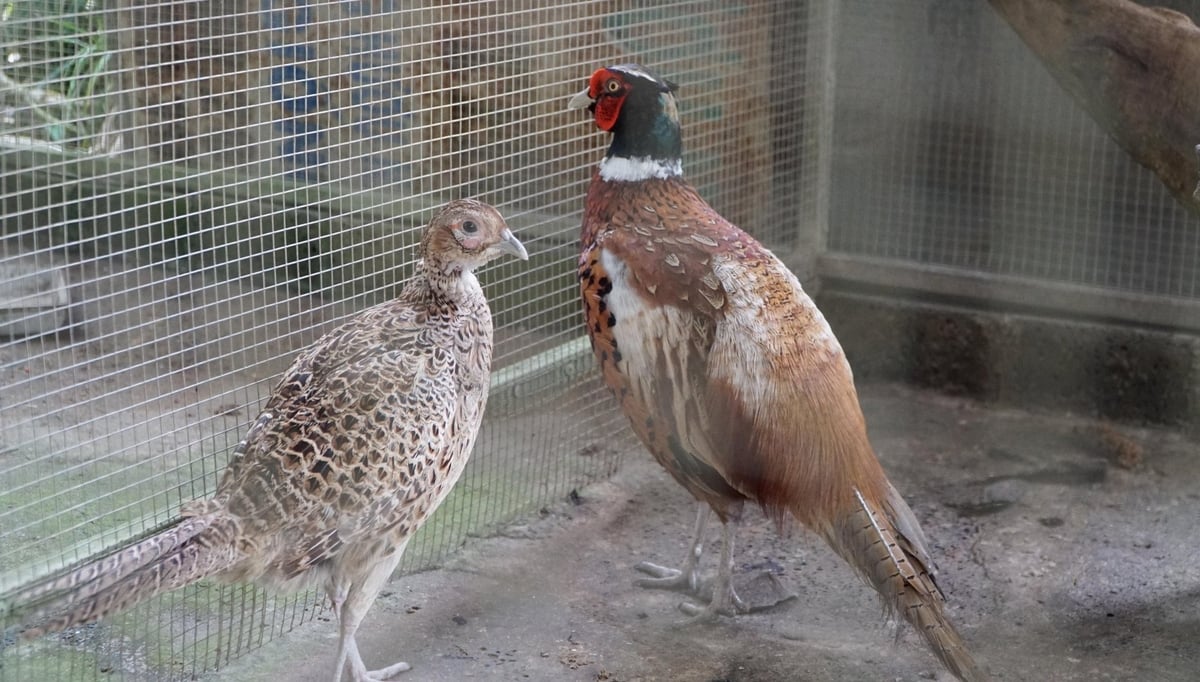

Among those adapting is Nguyen Van Truyen, who raises over 100 deer and pheasants in Hieu Liem commune. “We don’t have specialized wildlife veterinarians here,” he admitted, “but we’ve realized that if one animal gets sick, the impact goes beyond economic loss. It could affect the whole community. So even though it’s not mandatory yet, we’re proactively following preventive guidance”.

Local efforts are promising, but the broader question remains: How can Vietnam systematically integrate wildlife into its national disease surveillance framework?

In its 2023 report, the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) urged biodiversity-rich countries like Vietnam to develop in-situ and ex-situ pathogen monitoring networks for wildlife, unify data across forestry, veterinary, and public health agencies, mandate disease reporting in captive wildlife, and train veterinarians in wildlife-specific care.

Vietnam currently lacks a national wildlife health database. There is no consistent budget line for veterinary surveillance in national parks, and no requirement for regular health checks at captive facilities.

“We need to start by identifying who is breeding, caring for, and managing wild animals,” said Hien. “From there, we can build technical support systems, routine inspection protocols, and reporting mechanisms”.

Wildlife facilities must also be staffed with veterinarians trained in disease surveillance, who can regularly report to government agencies. Photo: Le Binh.

In parallel, Vietnam must establish a clear legal framework. Experts from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) recommend drafting a dedicated Circular on wildlife disease surveillance, akin to existing livestock vaccination and quarantine regulations. This new legislation should define responsibilities, procedures, and escalation pathways.

Beyond regulation, capacity building is critical. Currently, very few veterinarians in Vietnam are trained to treat species like monkeys, pangolins, bats, or gibbons. Laboratory infrastructure for wildlife sample analysis is similarly scarce. Without long-term investment in training and equipment, early disease detection will remain out of reach.

“There are species we outright ban from farming, but others are still legally raised”, Hien warned. “We fear outbreaks, especially when wild-origin animals are kept near traditional livestock like chickens, pigs, or cattle. If disease spills over, the consequences could be catastrophic. On top of that, many animals are farmed for entertainment, where biosecurity is often overlooked”.

The avian flu outbreak among tigers is only the tip of the iceberg. Disease from wildlife is not a question of “if,” but “when.” Every small effort, a capable rescue center, a private farm that reports symptoms, is a building block toward closing the gaps in our disease prevention ecosystem.

Translated by Linh Linh

(VAN) The North Central's dry climate and hilly landscape give it the potential to become a top pineapple production region, provided it capitalizes on its natural advantages and invests properly.

(VAN) Captive wildlife in Vietnam largely remains outside the official disease prevention system, exposing numerous species to uncontrolled risks.

(VAN) The death of 50 captive tigers due to the A/H5N1 avian flu in Dong Nai and Long An has underscored a void in epidemic monitoring within wildlife farming, which appears to be neglected.

(VAN) Anti-IUU efforts must be quantifiable: no vessels in foreign waters, full VMS coverage, and protection of fishing grounds and livelihoods.

(VAN) Implementing low-emission agriculture can only succeed when farmers trust the process and clearly see the tangible economic benefits of changing their cultivation methods.

(VAN) The shift toward low-emission crop production is seen as a strategic driver for enhancing the value of Vietnamese agricultural products and fulfilling international climate commitments.